REVIEW PAPER

Psychosocial occupational risk factors present in the work environment of paramedics

1

Urząd Marszałkowski w Warszawie, Polska

2

Ministerstwo Aktywów Państwowych, Warszawa, Polska

3

Szpital Matki Bożej Nieustającej Pomocy w Wołominie, Polska, Warszawska Uczelnia Medyczna im. Tadeusza Koźluka,

Warszawa, Polska

4

Uniwersytet Medyczny w Łodzi, Polska

5

Collegium Medicum, Uniwersytet Jan Kochanowskiego w Kielcach, Polska

6

Centrum Zdrowia Psychicznego LUX MED, Polska

Corresponding author

Med Srod. 2022;25(3-4):66-71

KEYWORDS

TOPICS

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objective:

Paramedics, due to the nature and character of their work, perform professional activities in exposure to psychosocial hazards. The impact of psychosocial hazards during the work process can negatively affect both physical and psychological health. Therefore, it is a serious problem not only of occupational medicine and public health, but also occupational health and safety. The purpose of this study is to present possible negative health effects resulting from exposure to psychosocial risk factors in the context of the work of paramedics.

Brief description of the state of knowledge:

The work environment of paramedics, in which there is an increased exposure to psychosocial factors, is associated with deterioration in the physical and mental health indicators of those in the profession. Psychosocial hazards cause increased levels of stress, occupational burnout, increase sickness absenteeism, or intent to leave the job. This also results in increased employee turnover, and reduced job satisfaction.

Summary:

The effects of exposure to psychosocial risks on the health of workers depend, among other things, on the work environment, type of activity, technology used and compliance with occupational health and safety rules and regulations. In order to minimize negative health effects it is reasonable to monitor the work environment to eliminate or reduce psychosocial risks and implement countermeasures at each stage of the work process. Monitoring psychosocial risks will improve the health of paramedics.

Paramedics, due to the nature and character of their work, perform professional activities in exposure to psychosocial hazards. The impact of psychosocial hazards during the work process can negatively affect both physical and psychological health. Therefore, it is a serious problem not only of occupational medicine and public health, but also occupational health and safety. The purpose of this study is to present possible negative health effects resulting from exposure to psychosocial risk factors in the context of the work of paramedics.

Brief description of the state of knowledge:

The work environment of paramedics, in which there is an increased exposure to psychosocial factors, is associated with deterioration in the physical and mental health indicators of those in the profession. Psychosocial hazards cause increased levels of stress, occupational burnout, increase sickness absenteeism, or intent to leave the job. This also results in increased employee turnover, and reduced job satisfaction.

Summary:

The effects of exposure to psychosocial risks on the health of workers depend, among other things, on the work environment, type of activity, technology used and compliance with occupational health and safety rules and regulations. In order to minimize negative health effects it is reasonable to monitor the work environment to eliminate or reduce psychosocial risks and implement countermeasures at each stage of the work process. Monitoring psychosocial risks will improve the health of paramedics.

REFERENCES (59)

1.

Expert Forecast on Emerging Psychosocial Risks Related to Occupational Safety and Health. http://osha.europa.eu/en/publi... (access: 11.01.2023).

2.

Nickell LA, Crighton EJ, Tracy CS, et al. Psychosocial effects of SARS on hospital staff: survey of a large tertiary care institution. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2004;170(5):793–798. doi:10.1503/cmaj.1031077.

3.

Kackin O, Ciydem E, Aci OS, et al. Experiences and psychosocial problems of nurses caring for patients diagnosed with COVID-19 in Turkey: A qualitative study. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2021;67(2):158–167. doi:10.1177/0020764020942788.

4.

Chmielewski J, Dziechciaż M, Czarny-Działak M, et al. Środowiskowe zagrożenia zdrowia występujące w procesie pracy. Med Srod. 2017; 20(2):52–61. doi:10.19243/2017207.

5.

Wypych-Ślusarska A, Grot M, Nigowski M. Zachowania mające na celu wzmocnienie odporności w okresie pandemii COVID-19. Med Srod. 2021;24(1–4):5–10. https://doi.org/10.26444/ms/14....

6.

Wypych-Ślusarska A, Kraus J. Postawy pracowników sektora ochrony zdrowia wobec epidemii COVID-19. Med Srod. 2022;25(1–2):21–27. https://doi.org/10.26444/ms/15....

7.

Chmielewski JP, Raczek M, Puścion M, et al. COVID-19, wywołany przez wirus SARS-CoV-2, jako choroba zawodowa osób wykonującychzawody medyczne. Med Og Nauk Zdr. 2021;27(3):235–243. https://doi.org/10.26444/monz/....

8.

Bielicki JA, Duval X, Gobat N, et al. Monitoring approaches for health-care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2020. doi:10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30458-8.

9.

Ilić IM, Arandjelović MŽ, Jovanović JM, et al. Relationships of work-related psychosocial risks, stress, individual factors and burnout – Questionnaire survey among emergency physicians and nurses. Medycyna Pracy. 2017;68(2):167–178. doi:10.13075/mp.5893.00516.

10.

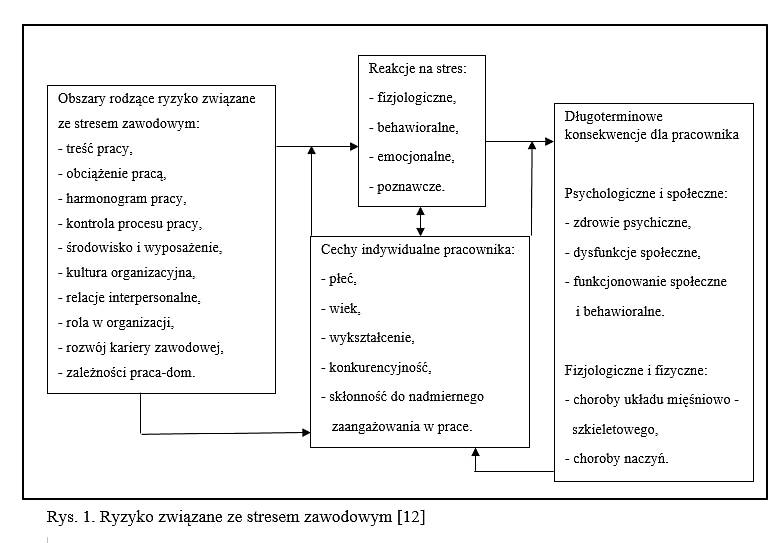

Fernandes C, Pereira, A. Exposure to psychosocial risk factors in the context of work: a systematic review. Rev Saúde Pública. 2016;50:24. doi:10.1590/s1518-8787.2016050006129.

11.

Mościcka-Teske A, Potocka A. Zagrożenia psychospołeczne w miejscu pracy w Polsce. Zeszyty Naukowe Politechniki Poznańskiej seria Organizacja i Zarządzanie. 2020;70:139–153. doi:10.21008/j.0239-9415.2016.070.10.

12.

Orlak K, Chmielewski J, Nagas T, et al. Zagrożenia psychospołeczne w pracy lekarzy weterynarii. Życie Weterynaryjne. 2013;88(10):827–876.

13.

Bajor T, Krakowiak M. Czynniki psychospołeczne a ocena ryzyka zawodowego w pracy strażaka. Prace Naukowe Akademii im. Jana Długosza w Częstochowie. Technika, Informatyka, Inżynieria Bezpieczeństwa. 2016;4:25–32. doi:10.16926/tiib.2016.04.02.

14.

Fedorczuk W, Pawlas K. Ryzyko zawodowe w pracy ratownika medycznego. Hygeia Public Health. 2011;46(4):437–441.

15.

Gragnano A, Negrini A, Miglioretti M, et al. Common Psychosocial Factors Predicting Return to Work After Common Mental Disorders, Cardiovascular Diseases, and Cancers: A Review of Reviews Supporting a Cross-Disease Approach. J Occup Rehabil. 2018;28:215–231. doi:10.1007/s10926-017-9714-1.

16.

Veromaa,V, Kautiainen H, Korhonen PE. Physical and mental health factors associated with work engagement among Finnish female municipal employees: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(10):e017303. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017303.

17.

Szarpak Ł. Znajomość zasad aseptyki i antyseptyki oraz przestrzeganie ich zasad jako elementów profilaktyki zakażeń w pracy ratownika medycznego. Med Pr. 2013;64(2):239–243. doi:10.13075/mp.5893/2013/0020.

18.

Gonczaryk A, Chmielewski JP, Strzelecka A, et al. Occupational hazards in the consciousness of the paramedic in emergency medical service. Disaster Emerg Med J. 2022;7(3):182–190. doi:DEMJ.a2022.0031.

19.

Chmielewski J, Galińska EM, Anusz K, et al. Ochrona pracy w zakładach leczniczych dla zwierząt w ochronie bezpieczeństwa i higieny pracy. Życie Weterynaryjne. 2015;90(07):427–430.

20.

Matuska E. Zagrożenia psychospołeczne związane z pracą. Studia nad Bezpieczeństwem. 2017;(2):129–142. doi:10.34858/snb.2.2017.010.

21.

por. Wyrok Sądu Apelacyjnego w Katowicach z dnia 14 marca 2019 r. Sygn. akt III APa 72/18. http://orzeczenia.katowice.sa.... (access: 14.01.2023).

22.

por. Wyrok Sądu Najwyższego z dnia 14 grudnia 2010 r. Sygn. akt I PK 95/10. http://www.sn.pl/sites/orzeczn... (access: 14.01.2023).

23.

Chmielewski J, Jackowska N, Nagas T, et al. Zawodowe narażenie na chemikalia w praktyce weterynaryjnej. Życie Weterynaryjne. 2015;90(11): 711–715.

24.

Kowalczuk K, Krajewska-Kułak E, Rolka H, et al. Psychospołeczne warunki pracy pielęgniarek. Hygeia Public Health. 2015;50(4):621–629.

25.

Stańczak A, Mościcka-Teske A, Merecz-Kot D. Zagrożenia psychospołeczne a funkcjonowanie zawodowe pracowników sektora bankowego. Medycyna Pracy. 2014;65(4):507–519. doi:10.13075/mp.5893.00055.

26.

Egan M, Tannahill C, Petticrew M, et al. Psychosocial risk factors in home and community settings and their associations with population health and health inequalities: A systematic meta-review. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:239. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-8-239.

27.

Chirico F, Heponiemi T, Pavlova M, et al. Zaffina S, Magnavita N. Psychosocial Risk Prevention in a Global Occupational Health Perspective. A Descriptive Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(14):2470. doi:10.3390/ijerph16142470.

28.

Chirico F. Job stress models for predicting burnout syndrome: a review. Annali dell›Istituto superiore di sanita. 2016;52(3):443–456. doi: 10.4415/ANN_16_03_17.

29.

Frimpong S, Sunindijo RY, Wang CC, et al. Domains of Psychosocial Risk Factors Affecting Young Construction Workers: A Systematic Review. Buildings. 2022;12(3):335. doi:10.3390/buildings12030335.

30.

Wischlitzki E, Amler,N, Hiller J, et al. Psychosocial risk management in the teaching profession: a systematic review. Safety and Health at Work. 2020;11(4):385–396. doi:10.1016/j.shaw.2020.09.007.

31.

Zakrzewska-Szczepańska K, Kurowska M. Wdrażanie dyrektyw Wspólnot Europejskich dotyczących bezpieczeństwa i higieny pracy do prawa francuskiego. Bezpieczeństwo Pracy: nauka i praktyka. 2001;4:14–17.

32.

Miller M, Opolski J. Bezpieczeństwo zdrowotne – zakres i odpowiedzialność. Problemy Higieny i Epidemiologii. 2006;87(1):1–5.

33.

Veromaa V, Kautiainen H, Korhonen PE. Physical and mental health factors associated with work engagement among Finnish female municipal employees: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(10):e017303. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017303.

34.

Kim KW, Lim HC, Park JH, et al. Developing a Basic Scale for Workers’ Psychological Burden from the Perspective of Occupational Safety and Health. Safety and Health at Work. 2018;9(2):224–231. doi:10.1016/j.shaw.2018.02.004.

35.

Väänänen A, Toppinen-Tanner S, Kalimo R, et al. Job characteristics, physical and psychological symptoms, and social support as antecedents of sickness absence among men and women in the private industrial sector. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;57(5):807–824. doi:10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00450-1.

36.

Santana LL, Sarquis LMM, Miranda FMA. Psychosocial risks and the health of health workers: reflections on brazilian labor reform. Rev Bras Enferm. 2020;73(0):e20190092. doi:10.1590/0034-7167-2019-0092.

37.

Chirico F, Ferrari G, Szarpak L, et al. Prevalence of anxiety, depression, burnout syndrome, and mental health disorders among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid umbrella review of systematic reviews. J Health Soc Sci. 2021;6(2):209–220. doi: 10.19204/2021/prvl7.

38.

Chirico F, Afolabi AA, Ilesanmi OS, et al. Workplace violence against healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. J Health Soc Sci. 2022;7(1):14–35. doi:10.19204/2022/WRKP2.

39.

Gonczaryk A, Chmielewski JP, Strzelecka A, et al. Aggression towards paramedics in emergency response teams. Emerg Med Serv. 2022;9(3): 155–161. doi:10.36740/EmeMS202203103.

40.

Gonczaryk A, Chmielewski JP, Strzelecka A, et al. Spinal pain syndrome incidence among paramedics in emergency response teams. Disaster and Emergency Medicine Journal. 2022;7(4):215–224. doi: DEMJ.a2022.0035.

41.

Chen WQ, Yu IT, Wong TW. Impact of occupational stress and other psychosocial factors on musculoskeletal pain among Chinese offshore oil installation workers. Occup Environ Med. 2005;62(4):251–256. doi:10.1136/oem.2004.013680.

42.

Ekpenyong CE, Nyebuk DE, Ekpe AO. Associations between academic stressors, reaction to stress, coping strategies and musculoskeletal disorders among college students. Ethiopian J Heal Sci. 2013;23(2):98–112.

43.

Larsman P, Kadefors R, Sandsjö L. Psychosocial work conditions, perceived stress, perceived muscular tension, and neck/shoulder symptoms among medical secretaries. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2013;86(1):57–63. doi:10.1007/s00420-012-0744-x.

44.

Van den Heuvel SG, van der Beek AJ, Blatter BM, et al. Psychosocial work characteristics in relation to neck and upper limb symptoms. Pain. 2005;114(1–2):47–53. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2004.12.008.

45.

Sterud T, Ekeberg O, Hem E. Health status in the ambulance services: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6(1):82. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-6-82.

46.

van der Ploeg E, Kleber RJ. Acute and chronic job stressors among ambulance personnel: predictors of health symptoms. Occup Environ Med. 2003;60(Suppl 1):40–46. doi:10.1136/oem.60.suppl_1.i40.

47.

Berger W, Figueira I, Maurat AM, et al. Partial and full PTSD in Brazilian ambulance workers: prevalence and impact on health and on quality of life. In Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2007;20:637–642. doi:10.1002/jts.20242.

48.

Haugen PT, Evces M, Weiss DS. Treating posttraumatic stress disorder in first responders: a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2012;32(5): 370–380. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2012.04.001.

49.

Halpern J, Maunder RG, Schwartz B, et al. Attachment insecurity, responses to critical incident distress, and current emotional symptoms in ambulance workers. Stress Health. 2012;28(1):51–60. 10.1002/smi.1401.

50.

Alexander DA, Klein S. Ambulance personnel and critical incidents: impact of accident and emergency work on mental health and emotional well-being. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178(1):76–81. doi:10.1192/bjp.178.1.76.

51.

Hansen CD, Rasmussen K, Kyed M, et al. Physical and psychosocial work environment factors and their association with health outcomes in Danish ambulance personnel – a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):534. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-534.

52.

Aasa U, Kalezic N, Lyskov E, et al. Stress monitoring of ambulance personnel during work and leisure time. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2006; 80(1): 51–59. doi:10.1007/s00420-006-0103-x.

53.

Boudreaux E, Mandry C, Brantley PJ. Emergency medical technician schedule modification: impact and implications during short-and long-term follow-up. Acad Emerg Med. 1998;5(2):128–133. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.1998.tb02597.x.

54.

Crowe RP, Bower JK, Cash RE, et al. Association of Burnout with Workforce-Reducing Factors among EMS Professionals. Prehospital Emergency Care. 2017;22(2):229–236. doi:10.1080/10903127.2017.1356411.

55.

Baier N, Roth K, Felgner S, et al. Burnout and safety outcomes – a cross-sectional nationwide survey of EMS-workers in Germany. BMC Emerg Med. 2018;18:24. doi:10.1186/s12873-018-0177-2.

56.

Grochowska A, Gawron A, Bodys-Cupak I. Stress-Inducing Factors vs. the Risk of Occupational Burnout in the Work of Nurses and Paramedics. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022;19(9):5539. doi:10.3390/ijerph19095539.

57.

Hegg-Deloye S, Brassard P, Jauvin N, et al. Current state of knowledge of post-traumatic stress, sleeping problems, obesity and cardiovascular disease in paramedics. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2013;31(3): 242–247. doi:10.1136/emermed-2012-201672.

58.

Braun D, Reifferscheid F, Kerner T, et al. Association between the experience of violence and burnout among paramedics. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2021;94:1559–1565. doi:10.1007/s00420-021-01693-z.

59.

Hegg-Deloye S, Brassard P, Prairie J, et al. Prevalence of risk factors for cardiovascular disease in paramedics. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2015;88:973–980. doi:10.1007/s00420-015-1028-z.

Share

RELATED ARTICLE

We process personal data collected when visiting the website. The function of obtaining information about users and their behavior is carried out by voluntarily entered information in forms and saving cookies in end devices. Data, including cookies, are used to provide services, improve the user experience and to analyze the traffic in accordance with the Privacy policy. Data are also collected and processed by Google Analytics tool (more).

You can change cookies settings in your browser. Restricted use of cookies in the browser configuration may affect some functionalities of the website.

You can change cookies settings in your browser. Restricted use of cookies in the browser configuration may affect some functionalities of the website.