Online first

Bieżący numer

O czasopiśmie

Archiwum

Polityka etyki publikacyjnej

System antyplagiatowy

Instrukcje dla Autorów

Instrukcje dla Recenzentów

Rada Redakcyjna

Bazy indeksacyjne

Komitet Redakcyjny

Recenzenci

2024

2023

2022

2021

2020

2019

2018

Kontakt

Klauzula przetwarzania danych osobowych (RODO)

PRACA POGLĄDOWA

Ostra nabyta ezotropia towarzysząca wywołana nadmiernym korzystaniem z urządzeń cyfrowych – przegląd literatury

1

Dolnośląski Szpital Specjalistyczny im. T. Marciniaka – Centrum Medycyny Ratunkowej, Wrocław, Polska

2

Wielospecjalistyczny Szpital Wojewódzki w Gorzowie Wlkp. Sp. z o.o., Polska

3

Wojewódzki Specjalistyczny Szpital im. Mikołaja Pirogowa, Łódź, Polska

4

Miejskie Centrum Medyczne im. dr Karola Jonschera, Łódź, Polska

Autor do korespondencji

Katarzyna Oktawia Skrzypczak

Dolnośląski Szpital Specjalistyczny im. T. Marciniaka – Centrum Medycyny Ratunkowej, ul. Gen. Augusta Emila Fieldorfa, 54-049, Wrocław, Polska

Dolnośląski Szpital Specjalistyczny im. T. Marciniaka – Centrum Medycyny Ratunkowej, ul. Gen. Augusta Emila Fieldorfa, 54-049, Wrocław, Polska

Med Srod. 2024;27(1):23-27

SŁOWA KLUCZOWE

DZIEDZINY

STRESZCZENIE

Wprowadzenie i cel:

Przez ostatnie dziesięciolecia, a w szczególności w ostatnich latach podczas pandemii COVID-19, znacząco wzrosło wykorzystanie urządzeń cyfrowych. Negatywnym skutkiem tego zjawiska jest eskalacja i zaostrzenie objawów cyfrowego zmęczenia oczu (ang. digital eye strain, DES). Do jego spektrum zaczęto zaliczać również ostrą nabytą ezotropię towarzyszącą (ang. acute acquired comitant esotropia, AACE). Celem niniejszej pracy jest przedstawienie najnowszych doniesień naukowych na temat ostrej nabytej ezotropii towarzyszącej i jej związku z korzystaniem z urządzeń cyfrowych.

Opis stanu wiedzy:

Długotrwała ekspozycja wzroku na ekrany urządzeń cyfrowych może prowadzić do zaburzeń jakości widzenia. AACE to zaburzenie charakteryzujące się wystąpieniem zeza zbieżnego o nagłym początku i dużym kącie odchylenia, któremu może towarzyszyć podwójne widzenie. Badania dowodzą, że schorzenie to dotyczy częściej młodych dorosłych, ale nie wyklucza się tego, iż może stać się udziałem dzieci lub osób starszych. Sugeruje się, że długotrwała praca w bliży wzrokowej, a zwłaszcza z wykorzystaniem urządzeń elektronicznych, prowadzi do wzrostu napięcia mięśnia prostego przyśrodkowego oka, następnie jego stopniowej spastyczności i w rezultacie do jego włóknienia. Ponadto niektóre badania potwierdzają możliwy udział krótkowzroczności w patogenezie AACE.

Podsumowanie:

Liczba rocznie rozpoznawanych przypadków AACE ma tendencję wzrostową i coraz więcej naukow-ców wiąże rozwój schorzenia ze zwiększoną liczbą godzin spędzonych przed ekranem urządzeń cyfrowych. Mimo to etiologia AACE zarówno w populacji dziecięcej, jak i u osób dorosłych nadal pozostaje niewyjaśniona. Ważnym aspektem jest edukacja i działalność prewencyjna DES oraz regularna kontrola wzroku.

Przez ostatnie dziesięciolecia, a w szczególności w ostatnich latach podczas pandemii COVID-19, znacząco wzrosło wykorzystanie urządzeń cyfrowych. Negatywnym skutkiem tego zjawiska jest eskalacja i zaostrzenie objawów cyfrowego zmęczenia oczu (ang. digital eye strain, DES). Do jego spektrum zaczęto zaliczać również ostrą nabytą ezotropię towarzyszącą (ang. acute acquired comitant esotropia, AACE). Celem niniejszej pracy jest przedstawienie najnowszych doniesień naukowych na temat ostrej nabytej ezotropii towarzyszącej i jej związku z korzystaniem z urządzeń cyfrowych.

Opis stanu wiedzy:

Długotrwała ekspozycja wzroku na ekrany urządzeń cyfrowych może prowadzić do zaburzeń jakości widzenia. AACE to zaburzenie charakteryzujące się wystąpieniem zeza zbieżnego o nagłym początku i dużym kącie odchylenia, któremu może towarzyszyć podwójne widzenie. Badania dowodzą, że schorzenie to dotyczy częściej młodych dorosłych, ale nie wyklucza się tego, iż może stać się udziałem dzieci lub osób starszych. Sugeruje się, że długotrwała praca w bliży wzrokowej, a zwłaszcza z wykorzystaniem urządzeń elektronicznych, prowadzi do wzrostu napięcia mięśnia prostego przyśrodkowego oka, następnie jego stopniowej spastyczności i w rezultacie do jego włóknienia. Ponadto niektóre badania potwierdzają możliwy udział krótkowzroczności w patogenezie AACE.

Podsumowanie:

Liczba rocznie rozpoznawanych przypadków AACE ma tendencję wzrostową i coraz więcej naukow-ców wiąże rozwój schorzenia ze zwiększoną liczbą godzin spędzonych przed ekranem urządzeń cyfrowych. Mimo to etiologia AACE zarówno w populacji dziecięcej, jak i u osób dorosłych nadal pozostaje niewyjaśniona. Ważnym aspektem jest edukacja i działalność prewencyjna DES oraz regularna kontrola wzroku.

Introduction and objective:

Over the past decades, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, the use of digital devices has increased significantly. A negative consequence of this phenomenon is the escalation and exacerbation of the symptoms of digital eye strain (DES). Acute acquired comitant esotropia (AACE) has also begun to be included in its spectrum. The aim of this study is to present the latest scientific reports on acute acquired comitant esotropia and its association with the use of digital devices.

Abbreviated description of the state of knowledge:

Drawn out visual exposure to digital device screens can lead to disturbances in the quality of vision. AACE is a disorder characterized by convergent strabismus with sudden onset and a large angle of deviation, which may be accompanied by double vision. Studies show that the disorder more often affects young adults, but do not exclude the involvement of children or the elderly. It has been suggested that prolonged near work, especially with the use of electronic devices, leads to an increase in the tension of the medial rectus muscle of the eye, followed by its gradual spasticity and eventually its fibrosis. In addition, some studies confirm the possible involvement of myopia in the pathogenesis of AACE.

Summary:

The number of annually diagnosed cases of AACE is a growing trend, and an increasing number of researchers are linking the development of the condition to increased hours spent in front of a screen on digital devices. Nevertheless, the etiology of AACE in both the paediatric and adult populations remains unclear. An important aspect is education and prevention activities for DES and regular eye check-ups.

Over the past decades, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, the use of digital devices has increased significantly. A negative consequence of this phenomenon is the escalation and exacerbation of the symptoms of digital eye strain (DES). Acute acquired comitant esotropia (AACE) has also begun to be included in its spectrum. The aim of this study is to present the latest scientific reports on acute acquired comitant esotropia and its association with the use of digital devices.

Abbreviated description of the state of knowledge:

Drawn out visual exposure to digital device screens can lead to disturbances in the quality of vision. AACE is a disorder characterized by convergent strabismus with sudden onset and a large angle of deviation, which may be accompanied by double vision. Studies show that the disorder more often affects young adults, but do not exclude the involvement of children or the elderly. It has been suggested that prolonged near work, especially with the use of electronic devices, leads to an increase in the tension of the medial rectus muscle of the eye, followed by its gradual spasticity and eventually its fibrosis. In addition, some studies confirm the possible involvement of myopia in the pathogenesis of AACE.

Summary:

The number of annually diagnosed cases of AACE is a growing trend, and an increasing number of researchers are linking the development of the condition to increased hours spent in front of a screen on digital devices. Nevertheless, the etiology of AACE in both the paediatric and adult populations remains unclear. An important aspect is education and prevention activities for DES and regular eye check-ups.

REFERENCJE (32)

1.

Pietrobelli A, Fearnbach N, Ferruzzi A, et al. Effects of COVID-19 lockdown on lifestyle behaviors in children with obesity: Longitudinal study update. Obes Sci Pract. 2021;8(4):525–528. doi:10.1002/osp4.581.

2.

Wong CW, Tsai A, Jonas JB, et al. Digital Screen Time During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Risk for a Further Myopia Boom? Am J Ophthalmol. 2021;223:333–337. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2020.07.034.

3.

Mohan A, Sen P, Shah C, et al. Prevalence and risk factor assessment of digital eye strain among children using online e-learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: Digital eye strain among kids (DESK study-1). Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021;69(1):140–144. doi:10.4103/ijo.IJO_2535_20.

4.

Mohan A, Sen P, Shah C, et al. Binocular Accommodation and Vergence Dysfunction in Children Attending Online Classes During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Digital Eye Strain in Kids (DESK) Study-2. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2021;58(4):224–231. doi:10.3928/01913913-20210217-02.

5.

Mohan A, Sen P, Mujumdar D, et al. Series of cases of acute acquired comitant esotropia in children associated with excessive online classes on smartphone during COVID-19 pandemic; digital eye strain among kids (DESK) study-3. Strabismus. 2021;29(3):163–167. doi:10.1080/09273972.2021.1948072.

6.

Kaur K, Gurnani B, Nayak S, et al. Digital Eye Strain- A Comprehensive Review. Ophthalmol Ther. 2022;11(5):1655–1680. doi:10.1007/s40123-022-00540-9.

7.

Coles-Brennan C, Sulley A, Young G. Management of digital eye strain. Clin Exp Optom. 2019;102(1):18–29. doi:10.1111/cxo.12798.

8.

Clark AC, Nelson LB, Simon JW, et al. Acute acquired comitant esotropia. Br J Ophthalmol. 1989;73(8):636–638. doi:10.1136/bjo.73.8.636.

9.

Mohney BG. Common forms of childhood strabismus in an incidence cohort. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144(3):465–467. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2007.06.011.

10.

Burian HM, Miller JE. Comitant convergent strabismus with acute onset. Am J Ophthalmol. 1958;45(4 Pt 2):55–64. doi:10.1016/0002-9394(58)90223-x.

11.

Bielschowsky A (1922) Das Einwartsschein der Myopen. Ber Dtsch Ophth Gesell. 43:245–248.

12.

Yagasaki T, Yokoyama Y, Yagasaki A, et al. Surgical Outcomes with and without Prism Adaptation of Cases with Acute Acquired Comitant Esotropia Related to Prolonged Digital Device Use. Clin Ophthalmol. 2023;17:807–816. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S403300.

13.

Hoyt CS, Good WV. Acute onset concomitant esotropia: when is it a sign of serious neurological disease?. Br J Ophthalmol. 1995;79(5):498–501. doi:10.1136/bjo.79.5.498.

14.

Lee HS, Park SW, Heo H. Acute acquired comitant esotropia related to excessive Smartphone use. BMC Ophthalmol. 2016;16:37. doi:10.1186/s12886-016-0213-5.

15.

Vagge A, Giannaccare G, Scarinci F, et al. Acute acquired concomitant esotropia from excessive application of near vision during the COVID-19 lockdown. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2020;57:e88–e91. doi: 10.3928/01913913-20200828-01.

16.

Neena R, Remya S, Anantharaman G. Acute acquired comitant esotropia precipitated by excessive near work during the COVID-19-induced home confinement. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2022;70(4):1359–1364. doi:10.4103/ijo.IJO_2813_21.

17.

Iimori H, Suzuki H, Komori M, et al. Clinical findings of acute acquired comitant esotropia in young patients. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2022;66:87–93. doi:10.1007/s10384-021-00879-9.

18.

Iimori H, Nishina S, Hieda O, et al. Clinical presentations of acquired comitant esotropia in 5–35 years old Japanese and digital device usage: a multicenter registry data analysis study. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2023;67(6):629–636. doi:10.1007/s10384-023-01023-5.

19.

Zhang J, Chen J, Lin H, et al. Independent risk factors of type III acute acquired concomitant esotropia: A matched case-control study. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2022;70(9):3382–3387. doi:10.4103/ijo.IJO_318_22.

20.

Cai C, Dai H, Shen Y. Clinical characteristics and surgical outcomes of acute acquired Comitant Esotropia. BMC Ophthalmol. 2019;19(1):173. doi:10.1186/s12886-019-1182-2.

21.

Okita Y, Kimura A, Masuda A, et al. Yearly changes in cases of acute acquired comitant esotropia during a 12-year period. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2023;261(9):2661–2668. doi:10.1007/s00417-023-06047-8.

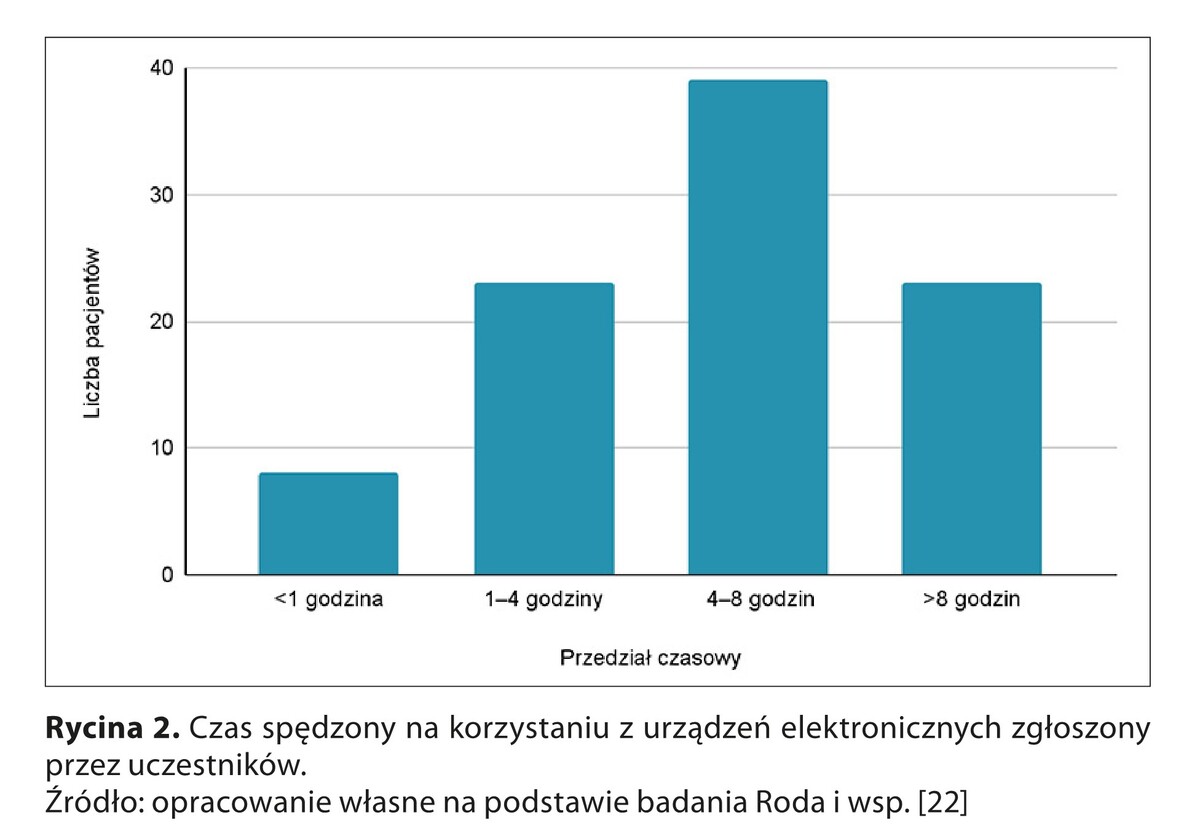

22.

Roda M, di Geronimo N, Valsecchi N, et al. Epidemiology, clinical features, and surgical outcomes of acute acquired concomitant esotropia associated with myopia. PLoS One. 2023;18(5):e0280968. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0280968.

23.

Van Hoolst E, Beelen L, De Clerck I, et al. Association between near viewing and acute acquired esotropia in children during tablet and smartphone use. Strabismus. 2022;30(2):59–64. doi:10.1080/09273972.2022.2046113.

24.

Mohney BG. Acquired nonaccommodative esotropia in childhood. J AAPOS. 2001;5(2):85–89. doi:10.1067/mpa.2001.113313.

25.

Nouraeinejad A. Neurological pathologies in acute acquired comitant esotropia. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2023;261(12):3347–3354. doi:10.1007/s00417-023-06092-3.

26.

Singh H, Singh H, Latief U, et al. Myopia, its prevalence, current therapeutic strategy and recent developments: A Review. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2022;70(8):2788–2799. doi:10.4103/ijo.IJO_2415_21.

27.

Ruatta C, Schiavi C. Acute acquired concomitant esotropia associated with myopia: is the condition related to any binocular function failure? Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2020;258(11):2509–2515. doi:10.1007/s00417-020-04818-1.

28.

Hayashi R, Hayashi S, Machida S. The effects of topical cycloplegics in acute acquired comitant esotropia induced by excessive digital device usage. BMC Ophthalmol. 2022;22(1):366. doi:10.1186/s12886-022-02590-w.

29.

Tong L, Yu X, Tang X, et al. Functional acute acquired comitant esotropia: clinical characteristics and efficacy of single Botulinum toxin type A injection. BMC Ophthalmol. 2020;20(1):464.doi:10.1186/s12886-020-01739-9.

30.

Padavettan C, Nishanth S, Vidhyalakshmi S, et al. Changes in vergence and accommodation parameters after smartphone use in healthy adults. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021;69(6):1487–1490. doi:10.4103/ijo.IJO_2956_20.

31.

Cai J, Lai WX, Li X, et al. Analysis of independent risk factors for acute acquired comitant esotropia. Int J Ophthalmol. 2023;16(11):1854–1859. doi:10.18240/ijo.2023.11.18.

32.

Alabdulkader B. Effect of digital device use during COVID-19 on digital eye strain. Clin Exp Optom. 2021;104(6):698–704. doi:10.1080/08164622.2021.1878843.

Udostępnij

ARTYKUŁ POWIĄZANY

Przetwarzamy dane osobowe zbierane podczas odwiedzania serwisu. Realizacja funkcji pozyskiwania informacji o użytkownikach i ich zachowaniu odbywa się poprzez dobrowolnie wprowadzone w formularzach informacje oraz zapisywanie w urządzeniach końcowych plików cookies (tzw. ciasteczka). Dane, w tym pliki cookies, wykorzystywane są w celu realizacji usług, zapewnienia wygodnego korzystania ze strony oraz w celu monitorowania ruchu zgodnie z Polityką prywatności. Dane są także zbierane i przetwarzane przez narzędzie Google Analytics (więcej).

Możesz zmienić ustawienia cookies w swojej przeglądarce. Ograniczenie stosowania plików cookies w konfiguracji przeglądarki może wpłynąć na niektóre funkcjonalności dostępne na stronie.

Możesz zmienić ustawienia cookies w swojej przeglądarce. Ograniczenie stosowania plików cookies w konfiguracji przeglądarki może wpłynąć na niektóre funkcjonalności dostępne na stronie.